HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN RAFTERS

From the mid-1600s on, England looked to its American colonies as a safe, alternative source of wood. The huge white pines of the New England colonies were particularly valuable, because they could provide the great masts and spars needed for Britain's battleships. When the American Revolution began in 1775, England was forced to come back.

The

founder of the Ottawa Valley industry was Philemon Wright, an immigrant

from Massachussets. He established a settlement at Hull, on the Ottawa

River. In the summer of 1806 Wright sent the first timber down the Ottawa

and the St Lawrence rivers to Quebec City. He had been warned that it

could not be done, because of the dangerous rapids. He succeeded by building

the timber into rafts. This was method used to move timber for the next

100 years.

In

that same year, 1806, the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte succeeded

in blockading the Baltic timber ports to English ships. By 1808 England's

imports had almost desapeared. In 1809 England turned to the North American

colonies for timber. As a result, in 1811, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia

between them exported nearly 280 000 cubic metres of pine timber. Quebec

City dispatched that year over 105 000 cubic metres of pine and oak timber.

The timber trade rapidly replaced fur as Canada's main export.

The

Baltic ports were reopened to English ships in 1812. However, the Canadian

trade continued. The British placed heavy tariffs in favour of Canadian

wood.

Fortunes were made in Quebec, and on the Ottawa River. Timber was big business. Timber making was hard, demanding work. Each autumn lumberers, as they were called before the term "lumberjack" came into use, went into the woods and built log shanty camps. Their fires for cooking, illumination, and for heat during the winter were simple stone hearths in the middle of the floor.They worked six days a week from dawn to dark. They had to make their own amusement. They were too far out in the woods to go to town.They could predict precisely where a giant pine would fall. Nevertheless, sometimes there were fatal accidents when the wind caught a toppling tree. In those days it was thought, wrongly, that the pine would last forever.

In

the spring, the logs were made up into rafts for the journey to ports

downriver. These were fitted together with wooden cross-pieces to make

a large raft.

On

the Ottawa River, the rapids were more dangerous. They had to use a more

complicated system. The basic unit was the "crib," made up of

20 pieces of square timber. A crib weighed about 40 tones. To get around

the rapids on the Ottawa River, timber slides, like water slides, were

constructed. When the rafts came to these slides they were dismantled.

The whole raft was then reassembled at the bottom.

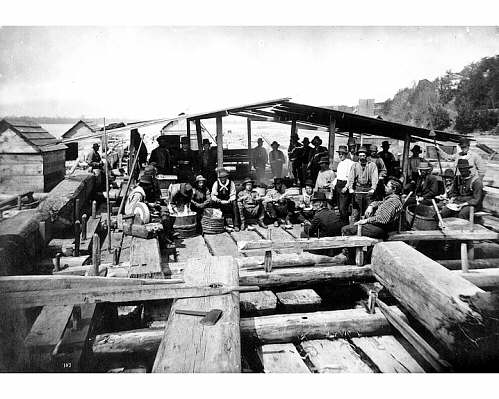

Some of the Ottawa rafts were half a kilometer long. They carried crews of 20 men who lived in huts on board the rafts. Their meals were cooked over open fires. Some 400 rafts came down the Ottawa each summer. Ontario had become the largest producer.

In

the 1860s, one of the first lumber camps in B.C. was established by Jeremiah

Rogers. It was on English Bay, in what is now the City of Vancouver.

The tremendous size of the trees of coastal B.C. called for new methods

of logging, for example in the 1890s little steam engines equipped with

cables and pulleys took the place of oxen. These engines grew in size

until logging sites began to look like outdoor factories. Huge skidders

gathered in logs over elaborate "skyline systems," with giant

pulleys and kilometres of steel cable. Since there were few coastal rivers

big enough to float the great Douglas fir logs, dozens of narrow gauge

railways were built.

While

B.C. "loggers" developed new methods, eastern Canadian "lumberjacks"

were busy with a new product that was to revolutionize the industry. Wasteful

methods had almost wiped out the white pine. However, the growth of newspapers

in the United States created a new demand. By the 1920s, pulp and paper

replaced lumber as the principal export.

Canada's forest industry is valued at $23 billion per year. It contributes more to the country's trade than agriculture, mining, petroleum, and fisheries combined. As long as continued care is taken in restoring and renewing our forests, forest products will be a source of Canadian wealth in the century to come.